The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s was an incredible and inspiring time in American history, where brilliant Black artists, writers, poets, intellectuals, and more reclaimed the African American narrative and developed a new cultural identity. Writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Alain Locke made history as part of the movement, but a lesser known artist of the Harlem Renaissance was actually one of the most influential American artists of the 20th century.

Augusta Savage, was a highly accomplished sculptor, an educator, and an activist who tirelessly used her platform to demand justice and equality for Black people in America, particularly Black artists. Her work was game-changing and her legacy continues to remind us how important it is to stand up for ourselves and peers in face of prejudice.

Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida. The daughter of a poor Methodist minister, she was drawn to sculpting from a young age, despite her father’s at times violent disapproval.

“From the time I can first recall the rain falling on the red clay in Florida,” she’s quoted as saying, “I wanted to make things. When my brothers and sisters were making mud pies, I would be making ducks and chickens with the mud.”

Growing up, she made a reputation for herself as a skilled sculptor. Her high school principal took notice of her talent and encouraged her to pursue art, and her work received a special prize at the West Palm Beach County Fair. In 1921, she journeyed to New York City with less than $5 to her name to pursue her dreams as an artist. She attended the scholarship-based Cooper Union in Manhattan, having beat out 142 other male applicants, and received further scholarships to cover room and board. As if that wasn’t impressive enough, she completed the four-year program in three years.

The prodigious sculptor excelled in portraits and was tasked with sculpting a bust of W. E. B. Du Bois for the Harlem Library and later, busts of Marcus Garvey, James Weldon Johnson, Frederick Douglas, and more. Known for capturing Black subjects, one of her most famous works was Gamin, a portrait of a Black child based on the likeness of her nephew. The piece, poignant and expressive, landed on the cover of the magazine Opportunity and led to more, well, opportunities to study abroad and gain more acclaim.

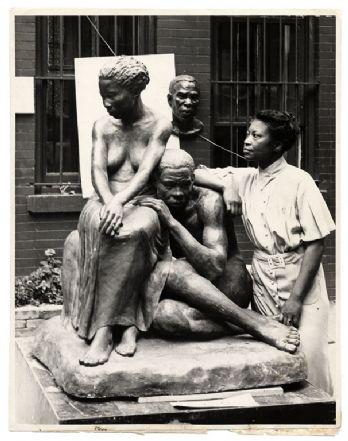

Courtesy Federal Art Project, Photographic Division collection, 1935-1942. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Despite these remarkable accomplishments and the recognition that came with it, Savage was still denied opportunities for simply being Black and a woman.

In 1923, she was awarded a scholarship to Fontainebleau School of the Fine Arts in France, but her acceptance was rescinded when the school realized Savage was Black. Her predicament was met with media attention and massive public support, but despite the pressure to change their decision, Fountainbleau upheld their decision. Savage wrote of the situation:

“I hear so many complaints to the effect that Negroes do not take advantage of the educational opportunities offered them. Well, one of the reasons why more of my race do not go in for higher education is that as soon as one of us gets his head above the crowd there are millions of feet ready to crush it back again to that dead level of commonplace thus creating a racial deadline of culture in our Republic. For how am I to compete with other American artists if I am not to be given the same opportunity?”

These frustrations led to a career of documenting and celebrating Blackness in her work — as well as a lifetime of creating spaces, platforms, and opportunities for other Black artists to thrive.

In the early 1930s, she opened the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, which later became the Harlem Community Art Center. Over 1500 students attended the school to learn various forms of fine art, including some of the most iconic artists of the Harlem Renaissance like Charles Alston, Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, Ernest Crichlow, and more.

On top of teaching, Savage dedicated herself to fighting for Black artists to be included in projects under the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project, part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. She also co-founded the Harlem Artist’s Guild in support of African American artists to “encourage young talent, to foster a relationship between artists and the public, and to improve artists’ standards of living and opportunities.”

In 1939, Savage was the only Black woman to be commissioned to create a piece for that New York World’s Fair’s Board of Design in what would become one of her most well-known works. The Harp, was a 16 foot sculpture inspired by the anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Even though it was said to be one of the most popular and photographed works that year, it was demolished along with the rest of the fair.

That same year, she was the first Black woman to open an art gallery which she dedicated to exhibiting Black artists. At the opening reception, she declared, “We do not ask any special favors as artists because of our race. We only want to present to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits.”

Courtesy New-York Historical Society. The John Axelrod Collection—Frank B. Bemis Fund, Charles H. Bayley Fund, and The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection.

Despite all her efforts and accolades, Savage’s career was hampered by financial difficulties as she worked to house and support her family. Many of her surviving pieces are in clay or plaster because casting them in bronze was too expensive. After her two galleries went under and Savage struggled under the pressure of financial difficulties, she left her illustrious art career behind and moved to Saugerties, New York, where she worked as a laboratory assistant and also ran a summer arts program. She died from cancer on March 26, 1962, in New York City at the age of 70.

Savage’s work brought grace, poise, humanity, and life to the portrayal of African Americans in art at a time when Black artists were absent from mainstream art and cultural spaces and contemporary depictions of Black people were rooted in racist caricatures and stereotypes. Though only a fraction of her work still exists today, they remain a testament to her belief that talent, hard work, and vision, transcends race — even when opportunity doesn’t. Her work is full of hope, expressiveness, and groundbreaking candid Blackness. Her legacy lies in her steadfast effort towards equality and autonomy for herself and the artists that came after her.

She fearlessly broke down barriers, becoming the first Black woman to do a number of things in her field — and working to make sure she wasn’t the last.

About the author.

Sam Mani writes about work, creativity, wellness, and equity — when she’s not cooking, binging television, or annoying her cat.